Notes on Mel Robbins –lessons to learn, habits to acquire, things to do (and things not to

do).

My personal trainerintroduced me to the work of motivational speaker and coach Mel

Robbins. She has posted many videos up on You Tube. I watched three,

taking notes and commenting as I went. Below is my first response,

blending my own personal experience into the key points raised. It's

a rough document, very much as written. I am a little short of time

at the moment, for reasons that will become apparent. Reflection and

revision will come later, after watching more videos.

I see that Mel Robbins isdescribed as a “best-selling author.” That's an appealing

description, for the very reason that I am a writer myself, a strange

kind of writer who has chosen to publish in free access rather than

commercially. That maybe ought to change.

I'll start with the firstvideo, on anxiety, and take each point as it comes. I'll then move to

a couple more videos, identifying a core theme and pattern as I go.

Mel begins by noting theobvious and familiar symptoms of anxiety: nervousness, restlessness,

feeling tense, racing heart, sweating, having a tight feeling in your

chest, the list goes on.

Every place I have workedwith others, indoors in offices or on the shop floor, I have

experienced these very things to an extreme level. Anxiety feeds on

itself to create a vicious spiral. You become paralysed, trying to

remain inert, in order to avoid sweating heavily, and it doesn't

work. You start to worry about personal hygiene and any comments that

others may be inclined to make. Which makes you even more nervous and

anxious, causing your heart to pump even faster. The situation is bad

for your mental and physical health, and potentially lethal, leaving

you with a chronic health condition.

Identifying the symptomsis easy enough, acting on them, and acting effectively, is more

difficult to do. I toughed it out for decades. Which is not the

wisest course of action.

Mel makes it clear fromthe start that her recommendations are for most people but not all.

People who suffer from acute anxiety need to seek professional help.

I am a person who has suffered from acute anxiety my entire life.

After suffering yet more issues with physical health I went to my

doctor in 2019 complaining of 'psycho-social anxiety.' She listened

patiently and suggested Asperger's or autism. In 2021 I was diagnosed

with ASC. The anxiety I had suffered and continue to suffer is

secondary to that condition. That said, I attended a couple of

anxiety classes, one in 2019 and another in 2020, and learned plenty

from both – being present and living in the moment, mindfulness,

meditation, breathing techniques, keeping a journal to objectify or

externalise your thoughts and then reflect back on them. Acquiring

such habits and practising them daily can help. It turns out that I

have since youth developed my own coping and survival mechanisms

which work – writing comes as easily as breathing to me. I also

love to hike or ramble, get outdoors into nature. But, as Mel makes

clear later, cleaving to survival mechanisms can hold you far short

of your dreams, desires, and potentials, ultimately thwarting your

talents and making you unhappy.

The need to survive comesfrom living in the face of uncertainty. Such is life. In my case the

uncertainty is made all the worse by the lack of internal filters and

editors, meaning that the world is present to me immediately at all

times as a whole. The result is sensory mixing and saturation,

leaving me overwhelmed and in retreat and paralysis.

What's the quickest wayto conquer uncertainty? Mel's answer to the question is to change the

story you're telling yourself.

Mel's story reads as verysimilar to mine, except that I have never taken medication for

anxiety. 'I have suffered from anxiety for most of my life,' she

says. Me too. I barely survived school. I got through university

simply by taking charge and taking over, dominating classes and

tutorials. It was hard work. I had to prepare hard, entering classes

with a battery of notes, all memorised to the last word. Imagine the

time that that took, imagine the energy it took. The brain is

high-maintenance. Although the brain is just 2% of body weight, it

accounts for 20% of the oxygen, and hence calories, consumed by the

body. You need to use the brain sparingly. Tendencies to

over-thinking need to be checked by some kind of ending point.

Without that check, the brain can run to infinity, exhausting the

body (I know, because this is precisely my problem).

Mel mentions that she wason medication for two decades from the age of 21, describing it as 'a

life saver' for her 'during some very dark years.' I have never been

on medication a) for the reason I never sought help, simply toughed

it out by grinding out results in my studies and work and b) I

refused it when offered it 2020. I prefer to make changes in the way

I live my life than rely on crutches. Mel says she suffered severely

from a depression 'that was so bad I could not be left alone.' The

question of depression cropped up with my doctor. The Patient Health

Questionnaires I completed recorded 'severe' and 'moderate'

depression at different times. Discussion indicated that the problem

was less depression in myself – it takes nothing to bring me back

to life and smiling – than in my very realistic and accurate

appraisal of my objective circumstances. The conclusion I drew there

is that it is less me that needs to change than the world … which

could take an awful long time.

Mel continues: 'when Ispeak about mental health and the struggles many of us face - I have

lived that nightmare, I have studied these topics.' Me too. She says

she has cured herself. I'm still trying hard, and failing. I have

spent the past couple of years reaching out for help only to find

there is precious little, only plenty of hindrance.

I've seen death anddestruction quite a few times in my life now. I was in the

Hillsborough Tragedy which led to the deaths of ninety-seven

Liverpool football fans. I went down the tunnel of death myself, but

had time to turn around and find another entrance point. I watched

the horror unfold from the next pen. I've seen some horrible things,

and suffered plenty, including a near fatal heart attack. Anxiety is

a wretched condition. Anxiety has been the biggest blight on my life,

stopping me from doing a thousand things well within reach of my

talents and abilities. Anxiety can steal your hopes and dreams, it

can steal your life away; anxiety can end your life. With three

degrees, from a first in history to a PhD in philosophy, politics,

and ethics, I should have been a top-flight academic. I could never

handle the workload. I would always over-prepare to make sure I had

every part of the brief covered. I could never handle classes, I

couldn't cope with constant demands and talking heads. Anxiety has

cost me a lucrative career. Anxiety almost cost me my life. Take

anxiety seriously. People who don't suffer from anxiety don't see the

problem and hence don't think it exists. Anxiety is the worst. Once

it gets a grip of you, it never lets you go. I fought it alone and

fought it to a standstill. When something is wrong, you have to find

the courage to admit to yourself and others that you have a problem

you have to identify what is wrong. And then you have to find the

courage to make changes, express vulnerability, and reach out to

others for help. It's the most courageous thing to do, not least

because most others are weighed down with struggles of their own and

lack the time and energy to help you out. I preferred to go it alone

and conquer stress and anxiety by racking up a series of

achievements. The problem is that such an approach generates stresses

and anxieties of its own. You end up on a never-ending treadmill that

goes nowhere, treading ever the harder as time goes by.

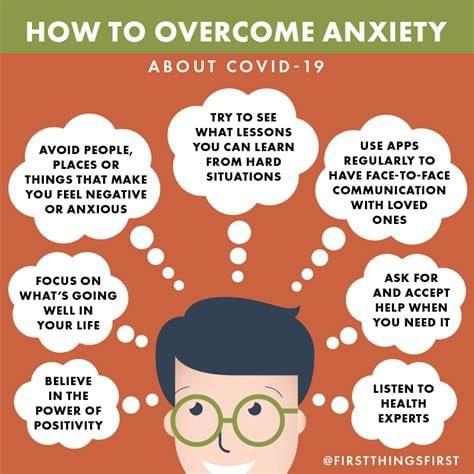

So what is the way out?'Habits' is a key word. There are good habits and bad habits. You

need to identify bad habits and start the process of converting them

into good habits. 'Anxiety begins with the habit of worrying,' Mel

says. (I am one of life's worriers). Through the act of worrying you

become locked into negative thought patterns that in turn trigger and

incite physical conditions. You become locked into a flight or fight

response, as if always being pounced on by lions hiding behind

bushes. The physical symptoms associated with that agitated state are

familiar - sweaty palms, racing heart, shortened breath. This is

anxiety. There is good stress and bad stress. Good stress incites you

into taking action in response to a threat. Once the threat has

ended, the warning systems stop sounding the alarm. Anxiety occurs

when the alarms continue to sound, leaving you in a heightened state

of alert. Intellect takes over from instinct, you start to over-think

and you never stop thinking. Energy is depleted and, in time, the

body comes to be exhausted.

The feeling is normal,Mel rightly says. What is not normal is when the body doesn't come to

fall back into a relaxed state.

What the quickest way todeal with it?

Mel says that the feelingcan be 'manipulated.' By this, she means that you can change your

thoughts and describe that agitated body state as something normal

and exciting.

OK, let's explorefurther. This sounds like turning negatives into positives, which

sounds good but is somewhat question begging. Positive energy, I

would say, is energy that should be channelled positively and

productively. That's not always easy to do when 'life' and its

relentless demands absorb your energy in so many negative ways. I

would recommend cutting out the negative and toxic as far as you are

able, keep the unproductive if it involves something pleasurable or

allows you to switch off and recharge.

Mel has something else inmind, asking us to stop being afraid of the unknown, to be curious

and pumped to learn.

That may well work …Each person is different. As an autistic person, living in face of

chaos and uncertainty and the unknown is the default position,

leaving me to crave regularity, order, and stability. 'You're not

nervous, you're excited,' Mel says. I like enthusiasm. Enthusiasm is

a great quality to nurture. But as an autistic person I get

'excitement' as a matter of course and need a little peace and quiet.

It all has to be tailored and tempered for me.

But I do like what shesays next: 'You're not fearful of the future, you can't wait to see

what the Universe has next.' You have to try to avoid becoming locked

into the past, as if the good or bad experiences long gone are all

that your life could ever be. Embrace the future and see what you can

do with it.

'Change the narrative inyour head and your body chemistry will follow suit.;

It's a simple science,Mel says. As a philosopher, I would also say it is the basic

Aristotelian ethics of habits, practices, and dispositions.

Character-construction, settling human beings within modes of conduct

and communities of practice. It is a key aspect of my philosophical

work.

Mel is all aboutstrategies for dealing with anxiety, showing people the way out.

I like the way that herwords are comprehensible and that the habits and practices she

recommends are accessible, within the reach of all who are struggle.

You can fix this 'one excited positive thought at a time.' I like

what she says next most of all: 'you do not have to do it on your

own.' My biggest worry with many 'positive' 'self-help' happiness

philosophies is that they can tend to focus heavily on the

individual. Individual responsible is hugely important. Successful

living, which we may call 'flourishing,' requires inner motive force

and agency. At the same time, there is a need to recognize that human

beings are social beings – we need each other in order to be

ourselves. Being alone and striving alone is often more than half of

the problem. I've done everything and more the self-help tough guys

demand, and it has simply worn me down.

Mel encourages us to asksome questions before identifying ourselves as someone who has social

anxiety. Sometimes, what seems as anxiety is merely a perfectly sound

reluctance on your part to join in with activities which you don't

enjoy:

💡 Is thatreluctance to go out just a sign that you prefer to be home?

💡 Does thenervousness just mean that you’re more interested in deeper

connections, not a frat party?

💡 Is theuneasiness about seeing people from your past just a recognition of

how much you’ve grown?

She describes herself as'a homebody at heart.' In a world made by and for extroverts,

introverts experience great stress in trying to 'fit in' and

participate in social action. That anxiety is the kind that can be

dispelled easily. What is right for you is right and you don't have

to measure up to the expectations of others or live in the opinion of

others.

Her next commentresonates deeply with me: 'I feel both excited to see people I like,

but also a weird feeling in my stomach about small talk with people I

don’t know as well.'

I do little talk, big orsmall, with people I don't know well, nor with people with whom I

seem to have little in common. I speak openly and excitedly with

people I like. It's a select group. I'm not being snobby or elitist.

People drain me. Social interaction and communication is difficult

for me, involving an inflation of information in all directions. So I

have to keep it tight to the select few I really like.

Mel's next sentence iskey and crucial and should be underlined:

'It took me a really longtime to embrace the fact that there’s nothing wrong with me.'

There is nothing worsethan going through life having to pretend to be someone you are not

in order to meet the expectations of others you don't really know and

don't particularly like.

'I just can’t standsmall talk. And I don’t care for big groups. I prefer deep

conversations with a handful of people.'

I love small talk withpeople I like; I can go as deep as deep can go with such people. I

avoid large gatherings. In parties I will be the quiet one on the

fringes wondering if I might be allowed to slip away now (now that

there is no more to eat!) For me, it's less a case of small or deep

talk as genial company.

The Secret to StoppingFear & Anxiety (That Actually Works)

NOVEMBER 21ST, 2022 |53:25 | E15

Let me move on to thenext Mel Robbins video.

She begins:

'I used simple researchfrom Harvard Business School and UCLA to tame my fear of public

speaking and become one of the most successful keynote speakers in

the world.'

Interesting. I wentthrough university and academic life being scared stiff of public

speaking, and I ended by being even more terrified. People told me

that I would get used to it in time and I never ever did. At one

point it led to a nervous breakdown. So as time passed, I reduced the

speaking to a minimum and then stopped. By the end I was having to be

dragged to speak in front of people.

You can overcome certainfears. Mel talks of overcoming her fear of flying. I had a fear of

flying. I never flew until 2014. I overcame the fear.

Fears that hold you backfrom doing the things you want to do can be confronted and overcome.

(Deep down, I know that I never actually wanted to speak in public or

become a teacher or lecturer, so had little inner motivation to

overcome the fears I had).

Your fears make youlesser than you are, limiting your horizons and diminishing your

potential. 'Anxiety robs you of happiness and confidence,' Mel says.

It robs you of all that makes life worth living; it can ruin your

life. She thus seeks to coach people through their biggest fears.

'Stop letting your fear make your life small.' Agreed.

'Board that plane, steponto that stage, apply for that promotion, and never let your nerves

stop you from living your life the way that you want to again.'

I think the key wordthere is 'want.' In the past, I had a tendency to try to overcome

weaknesses by becoming good at things I didn't really care about.

From being considered distinctly average at school, I became a

straight A student. I went on to university. I loved the grades and

the certificates but, it is clear, I saw them as forms of validation.

I never enjoyed academic life. In life terms, these count as wasted

years, years I could have spent doing something else, something I

enjoyed.

I move to the next video:

If You Struggle WithAnxiety, WATCH THIS! | Mel Robbins

Here, Mel begins bydeclaring that she was anxious, competitive, and insecure –

describing this as a deadly combination.

She mentions that a lotof her attitude was an outgrowth of an incident at school. I suffered

a lot of incidents at school. I was usually behind in classes,

learning at a different pace and in a different way. That made me the

target of abuse, verbal and physical. That abuse was systematic and

lasted years. I suspect that one reason I became so addicted to good

grades was because, deep down, I felt myself to be conquering my

adversaries and proving them to be wrong. You need to come out of the

tendency to live your life and exercise your talents in the opinion

of others, whether confirming others' expectations or confounding

them. Be true to your own potentials, your own dreams and desires.

Mel talks of dealing withinternal conflicts we have never resolved, creating 'survival

mechanisms' to keep you safe. The notion of coping mechanisms is

familiar to autistic people, helping us to negotiate an often chaotic

and noisy world, checking the ever-present danger of sensory

overload. The problem, as Mel says, is that whilst such mechanisms

can keep you safe and secure, you need to update the strategy as you

get older. If your life becomes geared to the operation of coping and

survival mechanisms, your potentials can lie fallow and go without

realisation. You may survive that way, but you will never thrive. A

life reduced to survival is no life at all. People need a meaningful

life, a reason to live, a purpose that drives them forward, a

direction, an enthusiasm. The problem with survival mode is that, at

some point, you ask the reason why and, finding none, collapse

exhausted.

Mel states that 'thenumber one thing that people are dealing with is unresolved conflicts

when they were young.' It's arguable that I never get over bad

experiences at school, developing as they did feelings of inferiority

and insecurity. She records that she employed her survival strategy

into adulthood. Again, I can see that I did the same. I can also see

that I redefined it in public as a success story, each top grade,

each qualification being presented as a triumph. In terms of a

practical working life, my academic successes never actually led

anywhere, except to more studying and more courses.

That competitiveness andstriving is grounded not in confidence and in your own natural

proclivities but in insecurity, in the need to prove yourself to

others. Mel makes a very good point when she says that 'people don't

catch your anxiety.' They see the outward signs of success and

conclude that you are a successful and ambitious goal-getter. That is

how I was perceived for years and I was more than happy to take the

perceptions of others as proof that I was flourishing well. Publicly,

I cut an impressive figure, privately, I didn't exist.

Mel next talks aboutgrounding mechanisms comprising a number of techniques. These

mechanisms are all about being present in time and space.

Technique number oneconcerns the physical aspects of living, holding someone's hand or

giving them a hug, centring them by touch. This can also involve

sitting close in front of someone and making eye contact. Getting

close to someone physically is therefore technique number one,

grounding a person by physical touch.

That may well work formost people. I have to add that autistic people may find such a

technique challenging, but not impossible. It depends on the person.

I tend to need a little warning but am fine with it all so long as I

am expecting it.

A long walk in thecountry also grounds you and calms you down. I do this a lot.

Technique number two isask people what they are feeling, emotionally as well as physically.

There is no need for an answer to this question. The questions are

not looking for answers and solutions but are merely about being with

a person.

Anxiety is all aboutuncertainty and, typically, that uncertainty concerns something a

person is unable to control in the present or the future. For

grounding techniques to be applied, let alone work, you need a

grounded and calm person in your life. Where are they?? And where do

such grounding mechanisms come from. You can talk about Buddhist

practices. There really doesn't have to be such discipline and

training. People innocent of learned wisdoms, but steeped in

experience, have learned the art of deep listening. Someone once

asked me what the wisest saying I had ever heard was. I couldn't

remember any one in particular so made one up on the spot: Keepyour mouth shut and ears open, learn what others have to say (and

learn that others do have something to say).

In the end it is simplyabout being in observance, with no need for judgement or resolution,

opening your eyes, ears, and heart to others.

Mel emphasises that'anxiety is not a disease.' By anxiety here she is referring to that

general anxiety that most people suffer from, and not acute or

chronic anxiety. The former can benefit from her techniques, the

latter need to seek professional help.

Her principal lessonconcerns action over waiting. It's about the actions you take. She

insists that the more consistently you take action, the quicker you

will start to believe in yourself, ceasing to be the kind of person

who sits around feeling unworthy and unhappy.

She repeats the pointover and again, it all starts with action.

I have some issues withthe next bit. 'Who is the problem?' Mel asks, eliciting the response

'I am' from the audience; 'who is the solution?' she asks, 'I am' say

the members of the audience. I'm not altogether sure that this is

entirely true. Since human beings are social beings, both problems

and solutions tend to be social in nature. I'm leery of personalising

social responsibility, just as I am leery of socialising personal

responsibility – this is a two-way process. You can't solve your

problems alone – a point that Mel makes herself elsewhere. But she

is right to say that a person is an active agent in his or her own

problem solving. That is the important lesson that she is hoping to

deliver here: remember that you are powerful, intelligent,

knowledgeable, and courageous agents who are able to take the

initiative and be proactive in seeking resolution: 'don't wait for

others.' This is important advice. If you wait for others you will be

waiting forever. I have actively sought out help from others, from

various authorities and organisations – there is next to no help

available, you are indeed on your own as far as the 'official' world

is concerned.

Mel next comes to peoplewho struggle with procrastination.

Procrastination is mymiddle name. I tend to defend procrastination as something that is

creative, an exploring of the full range of possibilities before

bringing an act to completion. Mel has something else in mind. She

notes that the people who struggle the most with procrastination are

PhD students, engineers, entrepreneurs, and such like, people who

have a lot on their plate, people who are juggling a lot of things,

people who are analytical in their approach, thinkers. Here I am! PhD

philosopher and writer. I am thinking all the time. Struggling with

procrastination can stress you out, Mel writes.

But procrastinationitself is not the problem. She mentions the phone calls you have to

make. You put them off, and spend the day worrying. You are exhausted

by the stress but have got nothing done. But it is stress rather than

procrastination that is the issue. With procrastination you are

taking a break. The way she describes it here, procrastination is an

avoidance strategy, an attempt to put things off until you feel

strong enough to deal with them.

She now comes tosomething that is music to the ears of an Aristotelian philosopher

like myself: habits.

Habits are important,habits are key. Flourishing well as a human being requires that the

cycle of bad habits is broken and replaced by the regular performance

of good habits.

Procrastination is ahabit that leads to avoidance and evasion. The problem is that the

break that you seek to take from stress can take over your life,

building up more problems and more stress.

Mel talks about creatingStarting Rituals, things that push you to start an activity. The

trick to breaking a cycle is starting. She recommends only working

for five minutes. Whilst this doesn't sound like being very

productive, it works like a trick. 80% of people who commit to

working for just five minutes will keep going. The trick is to get

started in the first place.

The trick works bybreaking the connection between the trigger, which is stress, and the

response, which is procrastination. Whenever you feel stress, know

that you have a choice and that choice is made in that five second

gap. In that five seconds the habit of procrastinating and beating

yourself up can take hold again, or you can choose to just get

started.

Mel comes to what shecalls 'hyperdrive.' She describes herself as an over-achiever,

someone who was a super busy go-getter because it won her praise and

attention. This is precisely my experience with my academic work. It

'also insulates you from other people,' she says. I ended up

elevating myself over others, intimidating them, even, and certainly

distanced from them. Far from resolving a problem, such an approach

makes a bad situation a whole lot worse. The 'hyperdrive to achieve'

comes from a feeling of inadequacy, she says. This accords with my

own experience. I gained recognition, respect even, but not

relationship. 'Being the best is annoying,' she says, 'a hangover

from something in the past.' The push to excel in academia stemmed in

part from an interest in the subjects of study, but largely from the

need to prove myself powerful and clever. It all came from a feeling

of inferiority that was developed into me at school. 'We walk around

thinking the same stuff from the past,' Mel says. You have to let bad

experiences from the past go. In seeking success as no more than a

triumph over the past, you never move forward.

'There is a gap betweenthe world and the things that trigger you and your response, and your

entire life is that gap.' This is the five second window between

instinct/stimulus and your reaction. Once you start to understand

that your whole life plays out in this five second gap between fear

and courage, between self-doubt and confidence, then you realise that

you have the ability to control it. Response is where your power

lies, in the possibility of choice - you get to choose what happens

in this small gap. When triggered, you get to choose whether to

succumb to an excuse or to push yourself forward.

She says that once youstart to speak up you will be 'shocked' and 'surprised' at the way

you will close the gap and make choices, exercising conscious control

over how you live. The magic happens in that gap between stimulus and

response.

A lot of times theproblem concerns the pattern of negative thoughts which tell you that

you are not good enough and not smart enough, and have you worrying

that this or that may happen. Ask yourself how such thoughts help

anything. A productive worry is a worry that motivates you to take

action. Good stress operates the same way. A destructive worry is a

worry that has you circling the drain mentally. You need to interrupt

destructive worry as soon as it starts to happen and send it packing.

If you are always thinking that you are not good enough, then you are

never going to believe the mantra that you are good enough. Mantras

work not by repetition but by belief; they don't work if you don't

believe them to be true. You need to break the chain of destructive

thoughts. Mel thus emphasises the power that lies in creating a

meaningful mantra. You need to be able to identify the patterns

whenever they appear and create a meaningful mantra. This is

empowering and serves to lift you up.

You can be paralysed byfear. The key is to break the pattern.

The next part is ofpersonal and very present interest to me. Mel asks us to identify the

'one thing you have been thinking about that you have stopped

yourself from doing.' She speaks of you being terrified of putting

yourself out there. She gives starting a business as an example. Yup.

I've been dealing with Business Wales these past three months with a

view to setting up my own publishing company, selling the dozens of

books I have written but made available in free access. I've been

stalling, looking at all the work it involves. It can be done. It

needs to be done.

'If you are stillparalysed,' she says, then 'you have not been able to change your

thinking pattern.'

This paralysis is changedthrough action. 'Because if you sign up for that class or go on that

retreat, if you post that blog, start that business, then you will be

proving to yourself through the actions that you are taking that you

don't care what other people think. Try that today.'

OK … but … I wouldphrase it differently. The action needs to be something that you

really want to do, rather than just proving a point. That's possibly

what she meant. It's just that in not caring for what others think,

there is no need to even mention others.

'What you are stoppingyourself from doing and what you are committing to doing today?'

Good questions. But becareful of seeing 'action' as such as a solution. Action in itself

can often be a neurotic response to pressures, feeling the need to be

busy to put your mind at ease. But the general message is sound

enough: find your interests, dreams, talents, and desires and start

to act on them. Identify what you want to do and start getting it

done – that's the surest way to break the paralysis.

Mel next comes to an oldbugbear of mine, the distinction between the things you can't control

and the things you can.

There are things youcan't control in the social or objective world, and the things that

you can control in your thoughts and actions.

I've never liked thisdistinction, for the reason it shifts the onus of responsibility upon

the person, completely ignoring societal and institutional

transformations that need to be made to make personal responsibility

and action possible, meaningful, and productive. We live in a social

environment. By placing the emphasis on changes that we can make as

persons, the social and institutional context is ignored. It requires

both. Many problems that we face have their origins outside of us, in

relation to others or in respect of social bodies and institutions.

Often, the emphasis on personal transformation reduces to

accommodating oneself to a world that inhibits and impairs your

potentials. There is a social and institutional agnosticism here that

is tantamount to resignation and cowardice. I know this from past

dealings with various organisations and authorities, employment

agencies who shift all responsibility to the individual agent when it

comes to finding employment, autism bodies which emphasise all the

changes an autistic person can make to adjust to an uncaring and

unchanging world. I've been here and done it to death. It can only

work to a certain extent, maybe enough of an extent for enough people

for its adherents to justify it as the best available approach. I've

always been one of the 'odds,' one of the exceptions, one of the

people whose talents get unrealised and wasted. And, for the record,

I have done everything required of me by various organisations and

agencies in the cause of self-help. They haven't worked and have come

close to wrecking my mental and physical health. It's not enough. The

social and institutional dimension has to be factored in rather than

ignored. It is lazy to simply claim that these cannot be controlled.

A distinction such as this makes a politically and sociologically

illiterate distinction between two essential aspects of human nature

– individuality and sociality. The social refers to human beings in

their collective identity. Whilst it is true that this cannot be

controlled individual and lies outside of the individual's power, it

can be transformed collectively. But that's politics. Teamwork makes

the dream work.

In terms of what theindividual can do for himself or herself in the here and now, the

advice is sound enough. Whilst the individual can't control the

supra-individual events and forces going on in the social world, he

or she exercise control in the gap between what is happening in your

life and work and what your reaction is to it. That gap, Mel says, is

five seconds long. 'If you understand that you can change what you

think, that you can change your habits, you can pivot and change even

the philosophy of your company, changing decisions, managing your

reactions, you will be unstoppable.'

Possibly.

There are aspects of yourlife that are energising and aspects which are depleting. If you are

not careful, you can get trapped in sterile grooves that tire you out

and keep you confined in a lane that takes you to a place you don't

want to be.

Everyone has a place tobe; everyone needs to know their place and know how to get to where

they need to be.

Mel describes her careeras a public speaker. For all the money she was making, it was

'depleting the hell' out of her. 'It's so important to pay attention

to what is energising you about your own business, because that's the

secret of seeing around corners.' She started to look around the

corner. 'To get to the next level of your business, you have to

decide right now what habits do you have as a leader do you have to

change now. Because you will not see around the corner, you will not

engineer the next quantum leap, unless you personally change.' This

was the process by which she went from being a speaker to writing a

number one book on Amazon. She did this by 'constantly innovating

myself.'

'I am the biggest singleproblem in my company, and if I don't constantly pivot and evolve

what I am focused on, I am going to be my blockade.'

Think where you want tobe and identify what habit you have to change to get there.

This is of directpersonal significance to me. I describe myself on my business card as

a speaker and tutor. I created that business card for my e-tutoring

business, Peter Critchley e-Akademeia. I no longer tutor and I have

long since given up public speaking, and didn't do much of it in the

first place. Speaking and tutoring are not things I enjoy and not

places I need to be. I am a writer. I have written over one hundred

books and made them available in free access. I am investigating

possibilities of creating my own publishing, “Writing Voice

Publishing,” to sell my books and make myself some well-earned and

hugely deserved money. Mel Robbins here has plotted my course. It

needs to be travelled. I need to get started.

You have to let go of thepast. If your mind keeps returning to the past, for fear of an

uncertain future, then you are going to be depressed. Because the

things that happened in the past cannot help you now. You can neither

change nor control the past, the only change and control that is

available to you lies in the here and now. Likewise, it you are

living in anticipation of the future, whether hopefully or fearfully,

then you are going to be in a state of constant anxiety, for the

reason that you are constantly thinking about things that haven't

happened yet and more than likely take place in ways that contradict

your expectations. 'Being in the present is where the gold is,' Mel

writes. 'Being in the present moment is where you will have the

greatest control, where you will have the most ease and where

happiness will flourish.'

40% of happiness levelsare set by genetics, 60% you are in control of.

Mel states that itdoesn't matter what has happened to you in the past. She claims that

some of the happiest and most grateful people in the world are those

who have had the worst things happen to them. Anyone who has read

concentration camp survivor Viktor Frankl's 'Man's Search for

Meaning' can confirm this. I can confirm it from personal experience,

having survived the horrors of Leppings Lane in the Hillsborough

Disaster.

The happiness that youare in control of comes down to your thoughts, your mindset, and your

attitude and you are 100% in control of those things. The key is to

develop the skill of being present in the moment, not in the past or

future, attuning your thought processes to the here and now where we

all live.

Be present.

You can learn thediscipline of being present by checking yourself whenever your

thoughts start to drift back to the past or forwards to the future,

showing a tendency to stay there. That's not where you are and not

where the people who can help you are.

Being present doesn'tnecessarily mean that the people you need are going to present

themselves immediately. They are there somewhere in the here and now,

I am told. They are few and far between in my experience. But they

are there and nowhere else. People are also stressed by struggles of

their own. Time and energy are scarce resources, and people tend not

to have much to spare. But here is the crucial paradox to grasp and

hold on to: energy, like love and power, is expanded by being shared.

By looking to others to lift your burden, you can help to lift theirs

in turn, establishing practices and processes of mutual aid. As a

result, we come to expand our being outwards in relation to others.

That's my concludingthought. You can do much by realising the power of your own agency,

you can be proactive and take charge and determine to turn your life

around. I will go with plenty that Mel Robbins says, and hope that

the little clauses and qualifications I have added don't cloud and

confuse issues to such an extent as to encourage a lapse back into

bad habits. You can take charge and take action, that's both simple

and true. But, speaking as someone who has been proactive my entire

life, as someone who has set high ambitions and realised them,

someone who went from the building sites to university and PhD, who

managed to just about cope with the stresses and strains of autism,

going undetected until just a couple of years ago, I'll just say that

there is no substitute for establishing warm, affective, mutually

supportive and meaningful bonds with significant others. Social and

emotional support is essential for flourishing well. And, often, in

the main, even, such connections merely involve the presence of

sympathetic others. Those others don't necessarily have to being

doing anything; usually, simply being there is enough. I have took

part in two courses on anxiety in the past, one in 2019 and one in

2020. I learned plenty from both. I made notes of the things that can

be done and ought to be done, which are plenty. I saw some people in

those classes who were in despair. One woman was clearing tearing her

hair out and picking at her scalp. It must have taken enormous

courage for her to simply turn up to class. That first step is always

the biggest one to take. She took the information home with her, paid

attention, joined in the exercises. The same with regard to another

woman who seemed depressed as well as anxious, suffering grief at the

loss of her mother. But my point is this: it was less the information

on anxiety that they received than the simple fact of joining with

others to express their concerns and share their experiences that was

the most uplifting thing of all. The truth is that human beings, as

social beings, need each other in order to be themselves.

The classes came to anend with the beginning of Lockdown. I shudder to think what became of

some of those poor ladies in the isolation that was to become our

common fate. But I praise their courage and bravery in joining with

others in public space to reveal their vulnerability and fragility.

We can talk about empowerment and agency and affirm our talents and

abilities to take charge and take action. And I would agree that we

can 'body-build' our capacities to be successful and self-determining

in the world. It is healthy and appropriate to stress the qualities

for successful living. But establishing warm and affective bonds with

others is at least as important a quality to nurture as any other.

The members of the anxiety classes I attended came to life in the

company of others, making it clear that they had been starved of

sympathetic ears. Everyone has a story to tell. The tragedy is that

not everyone has someone in their lives who is prepared to listen.

I have also noted theextent to which anxiety seems to affect women more than men. That

might just be a coincidence, an accident of my own particular

experience. I attended two different courses for anxiety, with just

one other man present for one, both courses led by women. Either

anxiety affects women more than men, or men are much less brave than

women, choosing to tough it out and hence suffer alone. It's not the

right way. I agree with philosopher Martha Nussbaum who writes about

'the fragility of goodness':

"To be a good humanbeing is to have a kind of openness to the world, an ability to trust

uncertain things beyond your own control, that can lead you to be

shattered in very extreme circumstances for which you were not to

blame. That says something very important about the condition of the

ethical life: that it is based on a trust in the uncertain and on a

willingness to be exposed; it’s based on being more like a plant

than like a jewel, something rather fragile, but whose very

particular beauty is inseparable from that fragility."

Martha Nussbaum, "TheFragility of Goodness"

I know all about anxietyand what it does to you mentally and physically. Living with a

relentless anxiety wears you down to such an extent that you tend not

to ask for what you really want, out of expectation that your desires

will not be met, having rarely been met in the past, and for fear

that refusal will destroy the little locked-away hopes and dreams

that keep you alive.

But, maybe, there arerisks worth taking, exchanging saving illusions for rich realities. A

greater joy lies that way. If you have the courage to believe that

life could ever get that good.

"Ever tried. Everfailed.

No matter.

Try Again.

Fail again. Fail better."

~ Samuel Beckett,Worstward Ho

In my assessment for AS,I said that over time I learned to keep trying, to keep working hard,

so that in the end I came to fail so beautifully that most everyone

took it to be success. I knew I was falling far short of all that I

could be and all that I ought to be.

You can turn that around.

Take anxiety veryseriously. Anxiety is a debilitating condition that can steal your

hopes and dreams, ruin your life, end your career, even end your

life.

I write further onanxiety here

Anxiety and Autism: Constant and Common Challenges

And here on my anxiety classes