A Year in the Life

It’s a year since I received the diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Condition.

The diagnosis has made no difference. I didn’t expect the diagnosis to be a golden key that opened the door to a happy and fulfilled future. I did expect that there would be at least some people out there who would offer at least some help, offering me some way of connecting with the social world in a way that fits my condition. Instead I found a lot of organisations and agencies with nothing to offer but advice as to how to ‘fit’ the unchanged and uncaring social world. I should name names. Those with hard experience of trying to negotiate the social world with autism will probably know them, or know similar.

My first inklings that things would not go smoothly was when I attended an interview with an employment organisation, with a view to finding suitable employment. I took my AS Report with me, with a view to leaving a copy of the reasonable adjustments and needs section, or at least having it read there. The person I spoke to didn’t respond to any of my promptings in this regard, so after twenty minutes or so I raised the issue directly and waved the Report in front of her face. She took it, feeling obliged, briefly scanned the relevant page at a distance, head back, and commented “we could all do with some of that.” This was someone in a position of authority on a work and health programme. This programme paid zero attention to health issues, these were for you alone to judge and deal with. If you made yourself available for employment, it was for you to select the appropriate jobs to pursue. All this programme did is supply a list of available jobs in your chosen fields. Anyone who knows how to access and search the various jobs’ sites can do this. I learned immediately that, as ever, I was the one expected to adapt myself and fit myself to whatever employment was available; there would be no adjustment from the outer world.

That was one organisation. I’ve had precisely the same experience with others. I’ve explained my needs to people working within these organisations and agencies. One explicitly claims to work with marginalised people in order to bring them into society, through work, through volunteering, through channelling any special interests and talents they may have etc. I met regularly with someone at this agency. I explained I have AS, I explained what that meant, giving examples that could be understood. I explained that I suffer from noise stress, wear ear plugs and headphones, avoid phones if I can. My preferred mode of communication is email. The person I spoke to was sympathetic, but made the common mistake of thinking that sympathy is the same as understanding and learning. He had understood and learned nothing. Quite simply, he had his own favoured modus operandi and refused to change it to accommodate my needs. So he would ring to make future appointments. That was almost tolerable. What was utterly intolerable was that, having gained an assurance from me that I would be available to meet at a certain time and date, he would deliberately avoid finalising the meeting place until ‘closer to the date.’ He was clearly juggling a lot of meetings, travelling from place to place, and so would only finalise at the last minute. That left me waiting endlessly for confirmation, even up to the early mornings of the proposed date. It caused me anxiety and sleepless nights. I put it with it much longer than I should have done. In the end, I pulled the plug on my landline, went to sleep, and determined never to have dealings with this character ever again. When I say that I suffer from noise stress, dislike uncertainty and disruption, avoid phone communication, prefer to communicate by email, I mean precisely that – I don’t mean that it is all open to adaptation and accommodation subject to the pressure and demands of others. I’m the one with eminently ‘reasonable’ needs and requirements which others need to recognise, not vice versa. I have found ‘society’ to be unaccommodating and uncaring.

My dealings with Remploy were thoroughly dispiriting. There was no attempt to determine my interests and abilities, no skills profile, no identification of my skills set, nothing. Instead there was a general chat that established my employability and then an attempt to fit me to whatever work was available. I suggested that companionship might be something I could do, given how well I got on with people in the community in my previous job (ten years in distribution, making it crystal clear I was employable). The people I dealt with had nothing to offer other than pressuring me into the best available fit. I enquired about companionship, they lined me up with care assistant jobs, jobs which are high stress, low pay, and hence have a high turnover of staff. I should know. My mother worked as a care assistant, I have other family members who have done the job, all of whom got out as a result of overwork. This was the very last job and environment someone with my needs should have been placed in. Remploy arranged interviews for me for Christmas Eve and Boxing Day, inflicting all manner of stress at Christmas, a special time of year for me. It soon became apparent that the company was suffering from staff shortage – I was told this bluntly. It was clear to me that there had been no attention paid to my own needs, skills, and requirements. Instead, the employment agency and the employer were serving their own interests, fitting me to their priorities. As I discussed one job on offer, the woman I spoke to clearly perceived I may not be suitable and so introduced me to other managers at the place with other available jobs. I expressed an interest – how could I not? I completed the application forms, sticking to the basic facts, stressing the weaknesses that could likely rule me out of contention, stressing my lack of experience in the area, and making no great appeal. The fact that I was invited to formal interviews in the first week of January should be taken as an indication that the company were desperate. The company rang me the morning of the first interview to tell me that they had had to postpone for a week. They claimed staff illness. The same thing happened with the other job I was due to be interviewed for. The same thing happened a week later. Then again another week on. I speculated that my applications were poor and the company was postponing in the hope of receiving better qualified candidates. I should have known from the moment I asked about deadlines in the informal interviews, only to be told that there weren’t any. I had a month of uncertainty and then withdrew the applications.

I was next set up with another wholly inappropriate job. Again it was clear I was simply fitted to whatever job was available. In the ‘interview,’ I was told that they couldn’t get staff. I was also told that staff had walked out without a word that week. I’ve written on this elsewhere. I shall simply say here that the job involved cleaning ladies’ toilets. All I can say is that these were infinitely superior to the men’s toilets. I found it stressful entering these quarters wondering who and what on Earth I would find in there, fearing being walked in on. I also had a reaction to working in corridors, close quarters, to the smells of the sprays, liquids, and powders. When I was invited to comment on the success of this employment agency in placing me in the job of my dreams, to be used as the poster-boy for Remploy, I hit the roof. There had been no attempt to guide me in employment terms. I had been given a job that was far worse than the one I had found by my own efforts and held for ten years before diagnosis. I had thought that diagnosis would enable me to get a better job, one suited to my skills, abilities, and interests. I was cleaning ladies’ toilets. And that was the most interesting part of the job.

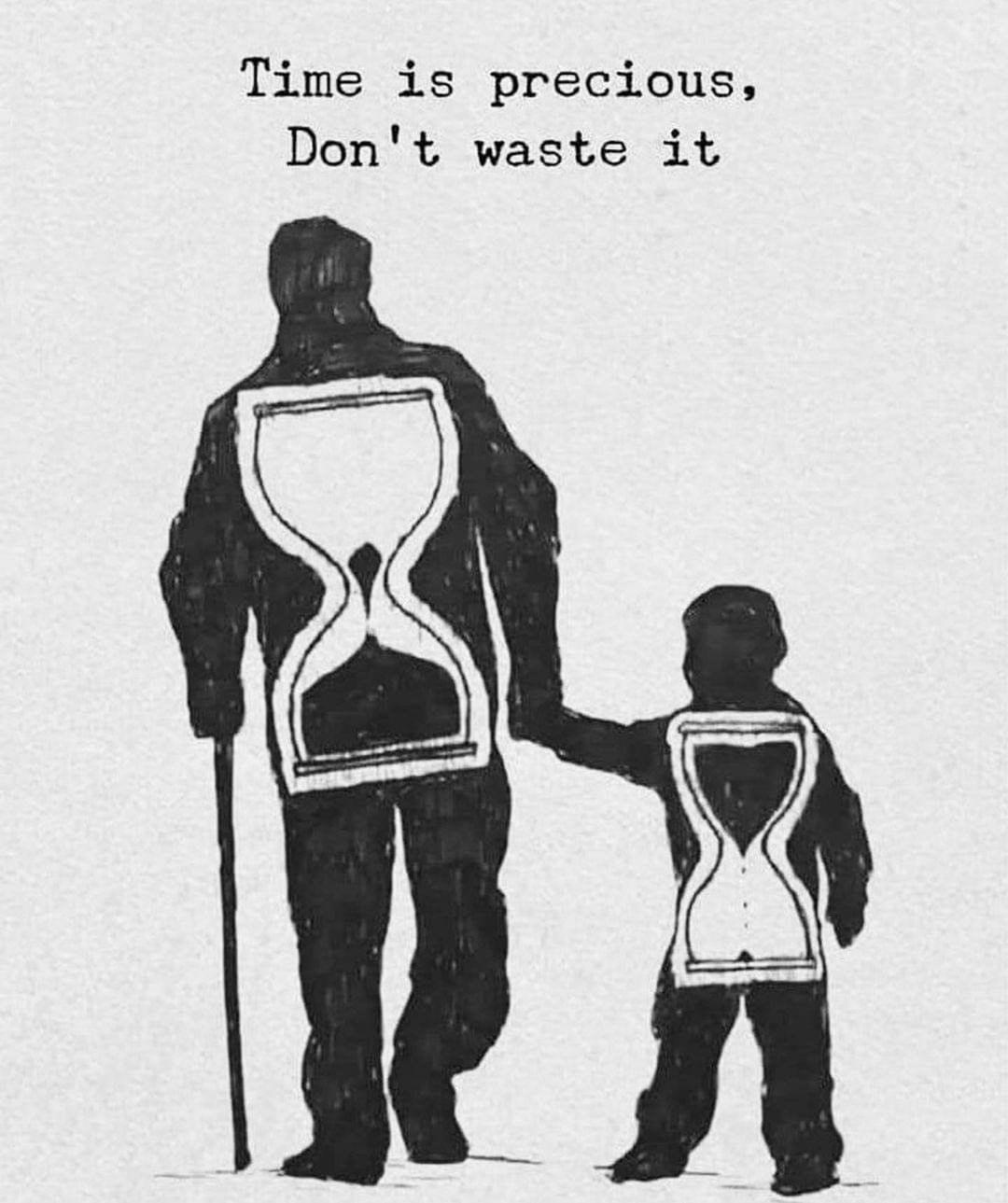

These events all took place between September 2021 and March 2022. That was a complete waste of my time and energy. I had lost the momentum that had come with diagnosis, and never got it back. I approached the Integrated Autism Service. It took them two months to respond. It seemed promising at first. But, again, it soon became apparent that the emphasis is upon personal rather than societal change, the things that I can do, in place of the things that ‘society’ ought to be doing. When I received praise for using headphones to deal with noise stress it became clear to me that all that the service could offer was advice on how I could manage my autism. I know how to do this. I am an expert at this. I have spent a lifetime managing my condition, dealing with its effects. We did a Star Chart, in which I scored highly for the way I managed my condition. The high score was reassuring in a way, but it made clear that this agency had nothing to offer beyond advice for self-management. I had approached them in the hope of social connection and opportunity. Instead, it was the same personalisation I have always experienced – CGT, breathing techniques, mindfulness. All these things cost ‘society’ nothing by putting the emphasis on personal change. This was utterly deflating. My road to diagnosis had come through the failure of anxiety-reducing techniques to touch my underlying problems, my doctor then suggesting referral for AS. I had come full-circle – the authorities have nothing and ‘society’ neither knows nor cares.

It should come as no surprise that less than 15% of autistic people are in full time employment, with only a tiny percentage of those working in fields they have interests in and talents for.

This is a scandal, an outrage, a same, and a tragedy.

The year I have suffered since diagnosis has reinforced the long, hard lesson of my entire life: there is no help, you are on your own, and people in an electronically abstracted and mediated world prefer to engage in lip-service to all nice things rather than the hard work of active service.

This time last year I had hopes and expectations of assistance in light of diagnosis. I am now without hope. Nothing has changed. I have long suspected that I was on my own: my experience of organisations, agencies, and ‘others’ this past year has confirmed that suspicion to be a realistic assessment of the objective situation. Whilst I am open to persuasion otherwise, it is wise not to live in expectation of helpful changes on the part of others.

For most of the year I wrote as an advocate for “Autism Awareness.” I now argue for “Autism Acceptance.” Awareness changes nothing. People acknowledge the existence of autism as a condition, feign sympathy (or express contempt for another ‘slackers’ alibi’), but make no changes in their behaviour. To be aware of something is not necessarily to understand it, and no changes in behaviour come without understanding and acceptance.

I don’t like to push. It is an age of pushy people. Pushy people get their way, even if it is not a way that most people find to their liking. A political activist ‘friend’ told me that ‘movements push and people follow.’ I have an innate, ingrained dislike of that view. It’s not just that I am one of ‘the people,’ it is that I am a singularly odd and eccentric member of the great public who has his own special way, one that works for me. I don’t care for educator-activists. They tend to know little beyond their own interests and concerns, which they prioritize over those of others (for their own good, of course). I have spent a lifetime being pushed by people who thought they knew my interests better than I did. I knew those people to be wrong, even if I couldn’t always articulate reasons in my defence. I would resist, and these people would push regardless. Frequently I was told to ‘grow up.’ People were expecting me to do things the way that ‘most others’ did things, without understanding that I was not ‘most others’ and that what worked for those others wouldn’t work for me. I needed help and understanding in finding my own way, but found helpful others to be thin on the ground.

For the most part I learned to keep quiet, not out of submission, but out of having no hope of being heard and understood. In the couple of weeks before my dad died he was being messed around by workmen who were supposed to be fixing his boiler. They gave times and dates but turned up as and when they liked, often after 5-30pm, clearly on their way back from another job. They were just fitting him in around their plans. And they didn’t do the job properly. So we were left constantly waiting. I told my dad that to get anywhere in this world you have to shout, shout, and shout again, and make sure you shout the loudest in a world that never stops shouting. He just nodded his head

in resignation in face of a bitter truth he couldn’t live by. He wasn’t a shouter, and neither am I. He wasn’t a pusher, either. And neither am I. We live in a world characterised by pushing and shouting, people with causes seeking to free-ride on the public sphere, circumventing the will and wishes of the actual members of the demos. Pushersand shouters are a charmless bunch, and know much less than they think they do.

If I may appropriate and adapt G.K. Chesterton’s The Silent People:

Smile at us, pay us, pass us; but do not quite forget;

For we are the people .. that never have spoken yet.

There are no folk in the whole world so helpless or so wise.

There is hunger in our bellies, there is laughter in our eyes;

You laugh at us and love us, both mugs and eyes are wet:

Only you do not know us. For we have not spoken yet.