Multitasking is a Myth

I once took part in a course on anxiety at a local adult community learning centre. I had gone along seeking advice on teacher training, but was informed of other courses that were starting that week. This class cropped up and it just so happened that the course leader was present. We chatted and got on well, so I thought why not, it’ll be a day out.

One of the classes dealt with stress and introduced us to stress-reduction and management techniques. The members of the class undertook a little exercise which sought to teach the lesson that ‘multitasking is a myth.’ It may well be. Multitasking is something that takes place when a person attempts to perform two or more tasks simultaneously, or switch immediately from one task to another, or perform two or more tasks in rapid succession. This is a form of mental juggling and is high energy and can be exhausting.

A number of studies have confirmed that multitasking, in the sense of doing more than one task at the same time, is a myth. People who think they are dividing their attention between multiple tasks at once aren’t doing that at all but are attempting single tasks at once, and doing them slowly and badly. It may look as though people attempting multiple tasks are getting more done, but the truth is they are doing less and getting stressed and worn out in the process. The people who multitask perform worse than those who attempt a single-task, removing value rather than adding.

That’s what any number of studies show. The class were given the reasoning and the evidence for it, with a view to calming our fears that we were incompetent and inadequate in some way for failing in our attempts to juggle several tasks in our lives. We were being relieved of our constant feeling of being overwhelmed, and cured of our neurotic urge to attempt too much and attempt even more in light of failure. This was a very good lesson to learn. We need to go easy on ourselves and stop putting ourselves under the pressure of impossible targets and expectations. You can’t do everything. One thing at a time, one day at a time is more than enough.

Agreed.

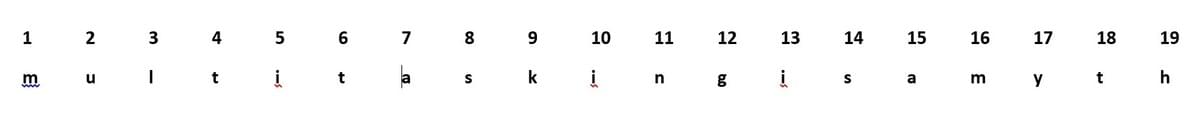

To reinforce the lesson, the tutor involved members of the group in atask-switching experiment, designed to give us a practical demonstration of the truth that ‘multitasking is a myth.’ We were put in pairs to conduct the experiment, each taking it in turn to carry the instructions out whilst the other observed and timed proceedings. We were asked to count how many letters are contained in the phrase ‘multitasking is a myth’ and then write these out 1-19 in a line across a sheet of paper. As one member of the pair did this, the other timed how long it took for completion. And vice versa. Then we were asked to write out the phrase ‘multitasking is a myth,’ again each timing the other. Both of these were single tasks, each timed. Then we were given the multiple task, writing the numbers 1-19 and the letters of the phrase ‘multitasking is a myth’ alternately, numbers on top, each letter placed directly underneath, continually switching as in 1 to m, 2 to u, and so on until completion. The slowing in timings was incredible, exceeding the two single experiments put together by a considerable margin. Except when it came to me. I went from 1 to m, 2 to u, 3 to l, 4 to t and so on ‘like a train,’ to use the words of the tutor. There was no pause for thought at all as I switched back and forth between numbers and letters with a speed and fluidity that the tutor found mesmerising. She stood transfixed as I unravelled her carefully constructed and successfully delivered lesson in a flash. She was hugely impressed and said that she had ‘never seen anything like it’ in all the times she had done the experiment with classes. She tried to salvage the situation by inviting me to volunteer the view that I had been ‘a little bit slower’ the second time round. I hadn’t, I had completed the multiple task at exactly the same speed as the two single tasks, at high speed, ‘like a train’ as she exclaimed most excitedly at completion.

I had ruined her experiment and unravelled her lesson. For me, there was no difference between single and multiple tasks. I was so busy basking in the general amazement my feat of high-speed switching had incited that I neglected to mention the cause of unusual ability – I have no internal filters and no editors, recognise no boundaries and borders, and have no brakes to apply as I run to infinity. That means that I see the world in its entirety and its immediacy, all interconnections as one. That normally leads to a feeling of being utterly overwhelmed, so much so that I have to close contact to others and the outside world, shutdown, delay, procrastinate, and suppress information. A simple task such as this is grist to the mill to me. Confronted with two simple strings of information, numbers and letters, is zero challenge to me, I put them together seamlessly, and so impress those watching. Others, I dare say, could perform the task with little difficulty (try to record exactly the same time as numbers and letters as two single tasks, if you can). The problem is that the vast quantities of information that everyday life generates far exceeds simple, discrete, definable strings and requires filters and editors to screen and parse, selecting the relevant and discarding the irrelevant. It is this that I struggle with. My mind wanders naturally, failing to weigh and balance information according to its significance and importance. That becomes enormously exhausting over time.