I’m lucid and eloquent when it comes to conversation. One-to-one, I speak freely and fluidly. I make this point to underline just how difficult it can be for people to understand the needs and requirements of a person who has autism. And remember that each person is unique, with very a very different set of needs and requirements. I can only speak from personal experience here with respect to the deceptiveness of my own condition. I am so skilled verbally as to give the impression of having no issues and no problems at all. I appear so confident in conversation that people will, naturally and unthinkingly, consider me ‘normal.’ Because I speak well, people will presume that I also listen well. Actually, no, not necessarily and not always.

I was an expert note-taker at university, learning to pick up on the stress, intonation, and timing of the speaker to identify and record essential information. But there is a big difference between taking notes in a lecture and absorbing the information that comes your way in a conversation. A lecture hall or classroom is a controlled environment where the communication is one-way; a conversation is a two-way process in an open relation. For an autitic person, the stress of dealing with social interaction consumes so much energy as to leave little over for receiving and recording information mentally. As a result, there can be a terrible struggle to retain information.

Like many autistic people I have a formidable long-term memory. I took to history like a duck takes to water. Many people find history boring and struggle with the demands that a mass of details make on the memory. I could absorb, assimilate, and evaluate information very easily, found the wealth of materials incredibly interesting, and went on to earn a first degree in history. When it comes to short-term memory, however, I am precisely the opposite. There may be a number of factors at play with regard to my weaknesses here. I dislike change, in fact I hate change. And I don’t cope well with the new at all. In fact, I have a tendency to blank out any information that doesn’t correspond with what I already know. It’s not so much that I have a tendency to forget such information but that I don’t recognize its existence in the first place. The reason for that is because I struggle to understand, read, and accommodate the new and the different. I cope well with the familiar, with those things I have succeeded in bringing into the orbit of my practical life. Refer to these ‘things’ and their requirements and routines and I will understand immediately. Refer to ‘things’ outside of the familiar, however, and the information will not easily be retained, precisely on account of being unfamiliar. And here’s the problem: because I am so eloquent, verbally, in conversation, people will not see that I could have an issue with verbal instructions and information that deviate slightly from my normal experience. How could they? I give no indication of having difficulty.

I argue not only for Autism Awareness but for Autism Acceptance, whilst recognizing what a tough – but necessary - ask this really is. Because autism isn’t some generic, one-size-fits-all condition. Each case will be different and there are definite limits to the expertise that others can have in learning of the particularities of each person. At the same time, there are sufficient common features in the condition as to make a ‘generic’ understanding available, accessible, and actionable.

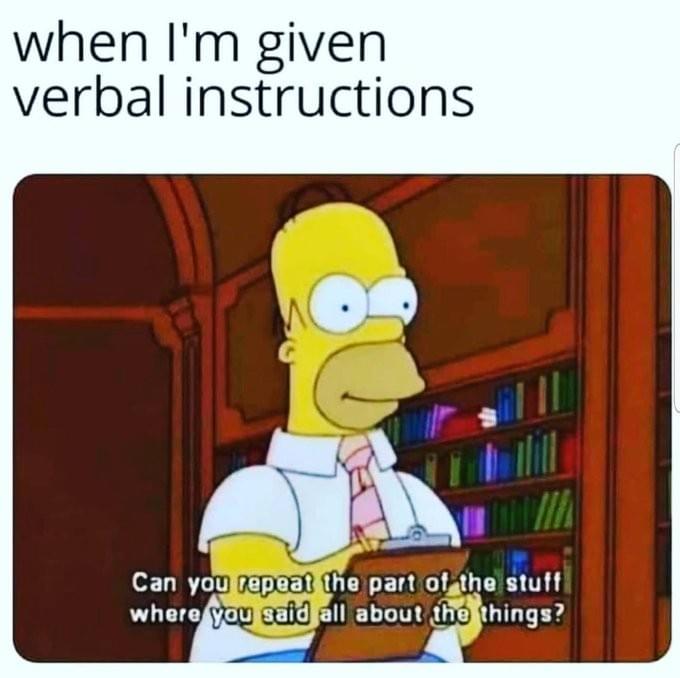

I, like many autistic people, struggle badly with any new information that comes my way, with changes in patterns and routines, instructions and orders, just new and different ‘things.’ This is particularly the case when the information is given verbally, whether face-to-face or over the telephone. For me, the interaction with others is stressful enough, absorbing all my energies in the act of engagement, above and beyond the actual purpose of that engagement. The actual information can be incidental to the encounter, becoming one great indistinct ‘noise.’ It takes all I have to negotiate my way through the encounter so as to survive to the end. Survival rather than absorbing any new information tends to be my goal in any encounter. Job done! Actually, no. For the reason that there are two very different jobs being done here, and the successful execution of the one might very easily be accompaniedby the complete bungling of the other. You may manage the encounter well enough, only to miss its purpose entirely. Many times when in receipt of information I have smiled, agreed, and nodded, feigning understanding so well as to fool the other person, who then proceeds to go away or put the phone down thinking that they have successfully imparted the information they have sought to impart. It’s only then, at conversation’s conclusion, that I come to realize that I have absolutely no idea of the meaning of the ‘things’ I have just been told and what I am now required to do in light of them.

Who’s fault is that? Seeking fault here is not a helpful way of proceeding. The blame game simply diverts us from seeing the problem clearly and accurately. The other person is attuned to the way that information is exchanged in ‘normal’ conversation, and so will expect you to understand or ask questions if you don’t. I think I can risk a generalisation from personal experience here. Autistic people can tend to be so out-of-step with others as generally to feel awkward and uncomfortable, doing almost anything and saying almost anything to mask their dis-at-ease and dissonance in an attempt to fit in rather than stand out. I rarely understood the new ‘things’ that came my way and, having learned the hard way that I struggled to apprehend and assimilate the new, sought to hide and avoid rather than ask questions in search of clarity and explanation. I learned early that I struggled to pick things up and preferred not to draw attention to my incomprehension. I was embarrassed many times in a classroom situation by teachers going over things I had failed to understand the first time round. It’s not a case of me being ‘slow’ and needing more time and practice to catch up, but a case of learning in a different way and processing information differently. Repeated attempts at the same explanation never succeeded for me, so I sought to avoid such exercises in futility by feigning understanding and refusing to ask questions. I didn’t ask questions because I learned early on that the same incomprehensible explanations would be offered. I knew it was futile and so masked my discomfort, performed my role, survived. It is not a case of learning at a different, slower, pace to others but learning in a different way. So teachers taking time to repeat the same explanation was no help at all, merely an ordeal I had to suffer in public, exposing me to the ridicule of others. So I learned not to ask questions and invite the same explanations, and I learned to be self-reliant and find my own way.

People in ‘normal’ conversation will offer information and expect people who struggle to understand to raise issues and ask questions. That’s not necessarily the way it goes with autistic people, if I may be so bold as to universalize a condition that is experienced in the particular. I experience such encounters as ordeals and my first priority in such situations is to survive and exit, the sooner, the better. The relief that comes with disengagement is soon overtaken by the worry that comes with the realization that the price of survival has been paid by me having missed the entire point of the encounter.

How could ‘normal’ others expect such idiosyncrasies on the part of neuro-divergent others?

It can come with education, awareness, understanding, and acceptance. All of which still begs the ‘how’ question. My only answer here involves reiterated encounter and ongoing practice within proximal relations to known, friendly, and familiar others. I have little faith in abstract authorities and agencies, charging people at remote distance with a general understanding of particular others. I’ve had dealings with such authorities and agencies and you are left picking through the advice and help they offer as best you can, separating what little may apply from the lot that doesn’t, avoiding complicity in the ‘same old’ like the plague it is. I insist that people never ever accept accommodation on account of it being all that is available. Know your needs, set your standards, and don’t compromise on them. Half-measures are no measures at all, they simply draw you back into the endless cycles of futility.

If you are lucky enough to find yourself in close relation and repeated encounter with others, my advice is to tell people this:

It is always good policy to have someone with autism repeat new information, orders, and instruction back to you, to ensure that they have understood the information they have been given and know what is required of them. Don’t take smiles and agreement as understanding, it may simply be the playing of a social role by way of masking. I have spent a lifetime doing this very thing, just to survive. I have observed social communication, interaction, and exchange from an external vantage point, like an alien anthropologist. You can see how people behave in social situations, see what is expected of people, and learn the rules of the human interplay. You can then put on a mask and a uniform and perform the role. I did this so well for so long that I was well into my fifties before my autism was detected and diagnosed. And the blunt fact is that I am not remotely a borderline case. I am a superb masker, performer, actor, and survivor.

In the end, my conclusion is that the onus of responsibility lies with the autistic person and with autism advocates. Because if you wait for others to get it you may well be left waiting a lifetime. Autism is too strange and too difficult a condition for hard-pressed others to grasp easily. If ASC is difficult to understand in a general sense, it is almost impossible for remote others to grasp in its particularities. I have little faith in abstract authorities andagencies and argue for reiterated encounter within proximal relations. Autistic people with autism respond best of all to familiar others, others who have the time and scope to understand the condition by way of repeated encounter. Sadly, this ideal is rare rather than the norm. So it is down to you to understand your needs and requirements, to know your rights, and to make your innate and experiential knowledge clear, known, and felt.